A good urban space is characterized by the number of people present in it and the positive interactions that arise between them. This is a clear and simple criterion.

The idea of measuring the quality of urban space through the density of people and the frequency of their interactions was first described by the well-known Danish architectural theorist Jan Gehl in his book “Life Between Buildings” (first published in 1971).

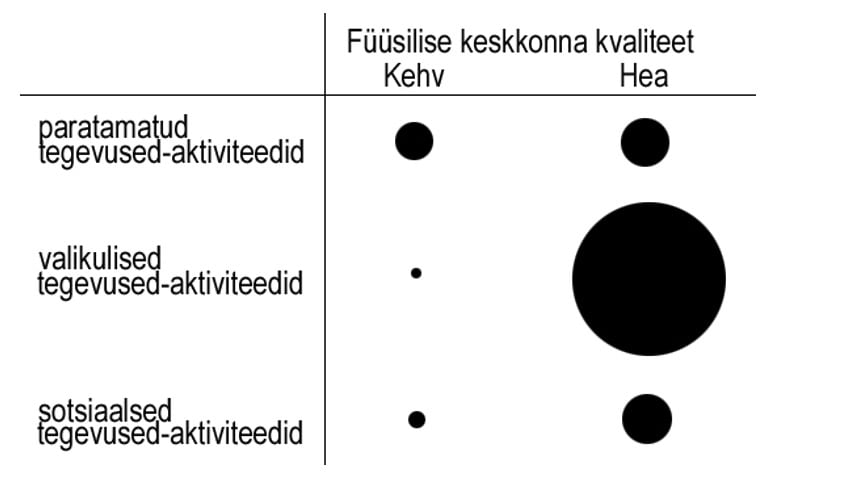

Gehl divides human activities in outdoor spaces into three categories:

- Necessary activities – these include things like going to school or work, shopping for daily needs, or waiting for a bus. In other words, they are everyday compulsory actions carried out regardless of weather, season, or the qualities of the urban environment.

- Optional activities – actions people choose to do when time, place, and mood allow, such as having a coffee in a corner café or taking a short walk instead of a bus ride.

- Social activities – these depend directly on encountering familiar people in public space and on the spontaneous interactions that arise from such encounters. They can be seen as an amplification of the first two types of activity when enough people gather in one place.

Gehl’s diagram on the relationship between urban space quality and its use illustrates how the true measure of urban quality is the number of people who spend time there. He also conducted detailed studies to identify the factors that attract or discourage people from using public spaces.

In his book, Gehl critically examines modernist residential quarters built in the 1960s and 1970s, especially their failure to properly understand or value public urban space and its quality. These housing districts were designed mainly around necessary activities – going to work, to school, to the local shop, and back to the warm apartment with a television. The main design value was ensuring optimal sunlight exposure for the buildings to provide adequate lighting. The quality of urban space was assumed to come from abundant greenery.

However, the existing street network – the skeletal framework of public space – was dismantled and replaced with a free-form layout pattern that was even claimed to draw inspiration from traditional belt ornaments. One might wonder whether Tõnis Vint would still admit today that Mustamäe’s free-form plan was inspired by Estonian national belt patterns, supposedly carrying a secret symbolic message.

It turns out that the greatest loss was the disappearance of the traditional street from modernist housing districts. The narrow street had successfully supported all three functions of public space: it allowed necessary activities while also generating incidental encounters that greatly enhanced optional and social activities.

Can the traditional street be restored in modernist housing areas?

Naturally, no.

Should we demolish the panel buildings? Perhaps yes!

But are there alternatives?

We cannot simply rotate buildings back to align with streets and roads. Lowering the building height, as has been attempted in some wealthier countries, might enhance the value of individual houses, but it would not necessarily improve the overall quality of public space.

The first issue worth addressing would be the main arterial roads connecting new housing areas to the city center. According to Gehl’s framework, these roads currently serve only necessary activities — direct routes from home to work or school, where the goal is simply to move as quickly as possible.

But what if these arterial roads were redesigned to focus on people instead of cars? Our new residential areas have streets that are far too wide. A comfortable street width should correspond to the distance at which a person’s face is still recognizable — according to proxemics, this is about 30 meters. The space between the buildings along Sõpruse Boulevard is about 70 meters. To achieve a more reasonable density, the boulevard could be divided in half.

In the middle, one could introduce a multifunctional row of buildings with commercial spaces, cafés, and shops on the ground floor, some offices on the middle floors, and new types of apartments with spacious terraces and glazed balconies on the upper levels. This would create a new street: one side following the principles of a traditional urban street, the other maintaining the open spatial character of modernism.

a cross-section of Sõpruse Pst. plan

This would liberate large areas of public space from cars and open possibilities for new optional activities — such as community gardening. While urban agriculture between panel buildings might at first recall the siege of Leningrad, when starving citizens grew food under their windows, this would actually align with the concept of “Rural Urbanism” — where the city moves toward the countryside, and the countryside moves into the city.

The guiding motto for the re-evaluation of our new housing districts could therefore be: the revival of streets and the discovery of new activities for residential courtyards.

architect Rein Murula